13 mars, 2023 lundi

34 degrees, cloudy

5-10 mph, NNW wind

On this cloudy and damp March afternoon, late winter garden work is at a standstill. Cold gusts of wind rattle window panes, forcing long days to be spent indoors. Hours spent house-bound offer a fitting time for reflection of the first two and a half months of this new year, along with our expectations and anticipation of what is yet to be. Mid-March, the Ides of March in ancient times, once signified the new year, a time which involved many celebrations and much rejoicing. Ides were ancient markers used to reference dates in relation to lunar phases. They refer to the first new moon of a month, which usually fell between the dates of the 13th and 15th. It seems like it was just yesterday that we closed out the old year and heralded in the new with the the French Colonial holiday celebrations, solemn and gay. The winter holiday celebrations of Le Reveillon and La Guiannée are age-old memories that are preserved in the present-day Illinois country. These modern celebrations hold within the long-ago visions of New Year’s Eve processions of costumed La Guiannée singers making their way door to door to offer song and New Year greetings and echoing cries of “Au gui l’an nuef! Mistletoe for the New Year!” The extant modern celebrations faintly echo the traditions of those French villages of the Illinois country centuries ago.

The first verse of the Prairie du Rocher La Guiannée song has its singers calling for mistletoe:

Bon soir la maitre et la maitress

Et tout le monde du logis

Pour le dernier jour de lannee

La Guiannée vous nous devez

Good master and mistress of the house

And the lodgers all, good night to you

For the last day of the ending year

The La Guiannée is to us due.

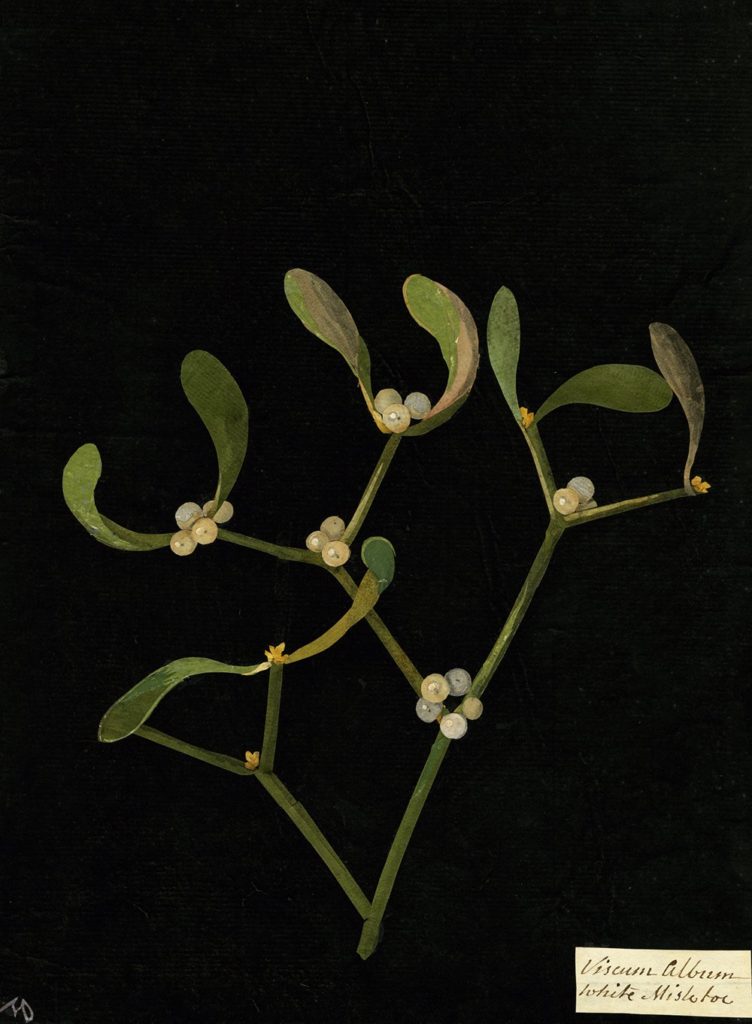

La Guiannée? A celebration demanding mistletoe for the new year? This celebration begs the question as to why mistletoe was so honored and coveted. The answer can be uncovered once again in ancient times, when mistletoe must have seemed magical in its ability to retain its green leaves, even growing white berries during the winter months, thus becoming a symbol of life, fertility, and prosperity. The archaic celebration of mistletoe has its roots dating from Celtic Druids of Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, traveling through the civilizations of Greece and Rome. Norse mythology heralded that this semi-parasitic plant was a sign of love and peace, while in the forests of medieval Europe, mistletoe was a plant that held extraordinary powers of life and health. Here in the new world, mistletoe (Phoradendron leucarpum) was a native plant existing in North America and regionally, right here in Illinois. Today mistletoe can be found in the southern one sixth of the state extending northward along the Wabash River to Clark County. Understanding this natural connection from the past to the present, helps us fathom how this tradition traveled from Europe with the early French colonists to the middle of the North American continent, known as Haute-Louisiane.

In an effort to appreciate the true nature of mistletoe, the center of these winter celebrations, one can look to its Latin name Phoradendron , which is Greek for “thief tree,” describing how this plant gets its nourishment from its host trees. Modern science has revealed mistletoe to be a semi-parasitic plant that utilizes photosynthesis and grows by taking water and nutrients from its host tree. Unusually, the plant grows in all directions at once and forms a spherical ball that can reach up to over three and a half feet in diameter. Its leaves are thick and quite tough; small flowers give rise in autumn to sticky white berries. The seeds contained in these berries are spread on the branches of trees by birds regurgitating or excreting the undigested fruits. Mistletoe can be found on any tree but mostly prefers soft woods such as apple, sycamore, ash, and poplar; rarely is it found on oak trees. In times past, herbalists called it “all-heal” and used it in infusions and teas to promote growth and cure infertility. The leaves, bark, and berries of mistletoe are now known to be highly toxic, so today its use only as decoration is warranted. In nature when found, the green winter’s growth of mistletoe brings a bit of welcome color to the brown and gray winter landscape. That color revealed by mistletoe’s presence in the heart of winter offers a reminder to those of us engaged in outdoor pursuits. It reminds us that the year’s journey which began in those new year’s celebrations, continues to bring us hope and the passage of these early months lead ever closer to the upcoming seasons of growth and bounty.

Well into the month of March, our focus has long turned from the winter holidays and the general winter landscape to our gardens and the preparations are underway required for the upcoming garden season. In-between the recent see-saw bouts of unsettled weather, there is a certain comfort in the return to basic garden tasks to be accomplished in winter. John Randolph, in his eighteenth-century “A Treatise of Gardening,” published in Virginia, offers the mid-winter advice:

“February

Sow Asparagus, make your beds and fork up the old ones, sow Sugar Loaf Cabbages* latter end transplant Cauliflowers, sow carrots and transplant for feed, prink out endive for seed, sow lettuce, Melon in hot beds**, sow Parsnips, take up the old roots and prick out for sees, sow Peas and prick them into your hot beds, sow radishes twice, plant Strawberries, plant out Turnips for feed, spade deep and make it fine, plant Beans.”

March

You should sow your Peas every fortnight, and as the hot weather comes on, the latter sort should be in a sheltered situation, otherwise they will burn up. I would recommend the sowing in drills about two or three inches deep, levelling the ground very smoothly with light mould, in rows about four feet asunder, for the convenience of going between, in order to gather the crop, and raising Cabbages or other things at the same time. In the spring let your rows be east and west, in the summer north and south, for a reason which must be obvious, viv. the giving them as much sun as possible in the first instance, and as little as possible in the last. When your peas are well up, they should be hilled once or twice before they are stuck; this not only strengthens them, but at the same time affords them fresh nourishment; the manner of sticking them everybody knows; I shall only therefore mention a caution to put your sticks firm in the ground, otherwise they are apt to fall, when the vines grow rampant, and not to stic on them in too near the roots, lest you do the plant an irreparable injury. In the spring it has been found that scattering some dry cow dung in the trenches before you sow your peas, has been very beneficial.”

Etching, 1557

In the Le Jardinier Solitaire written by French Carthusian monk Francis Gentil in 1704, recommends:

‘Work to be done in March-

…In wet Earth, Plant all sorts of Trees in this Month, Pear-Trees, Apple-Trees, Peach-Trees, Apricok-Trees and Plum Trees.

Continue to Graft in the Cleft.

Towards the End of the Month Soe in the naked Earth, all sorts of Sallating-Seeds, except Golden Purslane and also Seeds of Edible Roots.

Sprinkle Mould over Beds you have Sown, and Plant Asparagus.

Tho’ you had sown Peas in November and December, Sow more now, to have some when the First are gone.

Plant not out into the naked Earth till the Beginning of May, the Plants you have Raised in Hot Beds because the Earth ought first to be warm…*

If you have any Borders to be Planed with Pot-Herbs, or Sweet Herbs, fail not to do it about the End of this Month tho’ the Beginning of April is not too late.

The actual work that has taken place in the habitant jardin potager at Fort de Chartres in February and March is at a pace with the above eighteenth-century advice. Arriving at the mid-way point in March, the seasonal garden tasks of pruning the espaliered French heritage apple trees, pear trees, wild grapes, and the potager’s fruit shrubs is completed. The raised beds are being weeded and the soil turned, followed by the late winter’s first sowing of heritage runner bean, beet, cabbage, leek, lettuce, onion, pea, and spinach. As daylight stretches ever longer through the fluctuating conditions harbored within the month of March, there is a building of quiet anticipation for the upcoming growing season, full of all the hope and promise only a new year can bring. As winter fades with the long hours of darkness giving way to light, so do our visions of the early celebrations of this new year. The presence of these celebrations born in the cold and dark days of deep winter offers us an understanding that our present-day wants and desires are not so dissimilar to those of our region’s ancestors. We share a timeless hopeful yearning to be blessed with good health, vitality, and prosperity in the new year. Au gui l’an nuef!

*Cone-shaped head cabbages

** The hot bed allowed colonists to start vegetables before spring thawed the ground, protecting seedlings from the bitter cold and provides the heat needed for out-of-season growth. Gardeners would have layered soil over fresh manure from livestock to create a heat source. Once the manure cooled to seventy degrees F, the bed was ready for seeds. Straw placed on top provided protection from the elements. If prepared properly, the hotbed could retain its heat for several weeks.

Sources:

John Randolph, “A Treatise on Gardening.” 1760

Francois Gentil, Le Jardinier Solitaire, the Solitary Or Carthusian Gard’ner. 1706

Adam Lonice, Revised version of Eucharius Rösslin’s herbal. 1557

daily.jstor.org/beware-the-ides-of-march-wait-what/

blogs.illinois.edu/view/7362/490778

gardensalive.com/product/ybyg-winter-got-you-down-curl-up-in-a-french-hot-bed

britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/people-behind-collection/mary-delany

Photos CK

Recent Comments